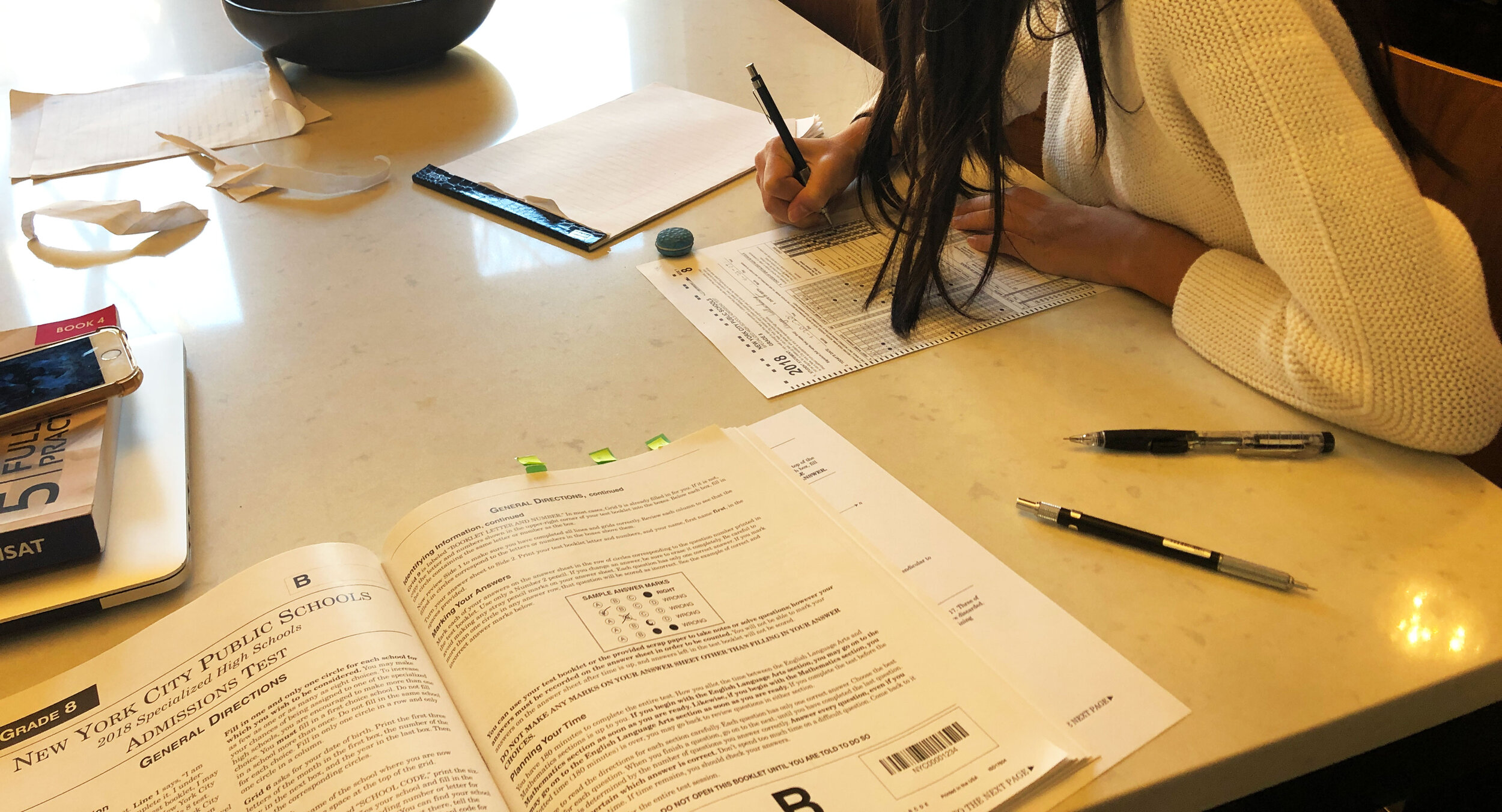

My daughter prepared for the SHSAT during the height of Covid – I helped

Like a lot of New York City dads, I wanted to help out my kid. So I studied the study materials, bought the books, and read up as much as I could. If you’d like to read the full story, it’s described here. For a brief recap, just scroll down.

Give yourself a minimum 6 month runway to prepare

If the test is in November, you need to begin prepping no later than May 1. My daughter and I started earlier than this, but we weren’t consistent during the summer. We got very lucky because the test date got pushed back due to Covid.

Commit to frequent small increments of study sessions

Frequent small increments of test prep is the technique my daughter and I used, and it worked for us. It’s also endorsed by the American Psychological Association. To use an analogy, brushing your teeth for 2 minutes twice a day is much better than 2 hours once a month. Although the total time investment is exactly the same – 120 minutes – the benefit is not. Not even close. Preparing for the SHSAT is the same: do it frequently in small doses.

Drill down on the skills you’re bad at, and skim (or ignore) the things you’re an expert at

You don’t have limitless time to prepare, so you’ll have to prioritize. Early on, my daughter and I identified the key areas that she was really weak in. The only way to do this is to take an entire assessment, then score the result. Tally up the ones you got wrong, and look closely for any patterns.

I took the time to carefully analyze her initial assessment by question type, and it was well worth it. When I did this, I was surprised. For example, my daughter was having difficulties with the fundamentals of Pemdas, and as a result, this was spilling over into other areas, like Word Problems. Obviously, understanding what you’re not good at informs how you ought to prepare. I made a list of weak areas, then structured a program around sharpening all of those skills one-by-one.

Reassess yourself often – not doing this is like letting someone give you a haircut without the help of a mirror

I wanted to know if what we were doing was making a difference. So I checked on a weekly basis. And it was working! Here’s how I did it…

At the beginning of the week, we agreed to focus on 1 or 2 skills on the list of weaknesses (for example: Pemdas and Probabilities)

I put together “mini’s” – groupings of between 5 and 15 problems that she worked on 3 or 4 nights out of the week. This usually took no more than 10 minutes. By the way, the mini’s never had repeating problems, so she couldn’t just memorize the answers.

Each time my daughter completed a mini, she and I reviewed the results and talked about the ones she was getting wrong (if any). If she was getting fewer wrong, I pointed that out. Without exception, she was moving in the direction of getting none wrong.

What I learned is this: when you take the time to thoroughly go over a single concept (like order of operations) in small doses, you start to see the gradual lessening of difficulty. Seeing that happen is proof of success, and experiencing success is contagious. My daughter could actually see herself getting better at a skill that was once scary. This idea isn’t rocket science: it’s brushing your teeth twice a day, applied to studying.

Allow time for goofing off – especially toward the end

Similar to marathon training, people need to be able to take their foot off the gas at some point before a major performance is expected (like peak conditioning). My daughter and I did our best to make this happen a few weeks before the test. During that time, I made it a point to get in some quality goofing off time with her, watching movies and sleeping in late (a few times). I highly recommend this.

In sports science, this type of controlled cheating is called tapering – and it’s a form of performance tuning that is proven to work over and over again. It allows people to reap the rewards of hard work (healing & recovery) by drastically reducing the primary source of stress: training. It’s the same for students. There is no trick. You just have to do the work. And just like brushing your teeth, doing the work in small manageable increments is more sensible.

Who I am and why I care

I’m a software engineer who specializes in automation: making the process of building and deploying software faster and more reliable. I’m pretty good at the internet. Plus, I understand your frustration as a parent of a New York City middle schooler.

One of my biggest frustrations in helping my daughter prepare for the SHSAT was not being able to find enough quality sample questions that closely mimicked the test. Over the course of a year, I think I’ve solved that problem, using open source software. I’m still tweaking it, but I’d like to share what I’m building with other parents and students. When you sign up for the newsletter, you’ll get free access to early versions of it as soon as it’s ready. I just ask that you be open to providing some feedback once in a while when I ask.

One last thing––my mom never got a chance to complete school. Her “childhood”—if you could call it that—was mostly spent protecting her brothers, and scrounging up food during and after the Korean war. My dad was a career soldier who volunteered twice for service in Vietnam. When we arrived in the US, my parents worked hard to send me and my sister to a fancy private school that cost half of what my dad made in a whole year as a staff sergeant in the Army. They each took second and third jobs. They didn’t complain, and it was never a topic of discussion. They just wanted the best for me and my sister.

I’d like to think that most New Yorkers are a little bit like my parents—which is maybe why you’re here.